While climate change has been known about for many decades, the effects are beginning to be felt now. Across Tasmania, there has been a decline in average annual rainfall since the 1970s, with the most notable decline in autumn. Increasing evaporation from a warming climate, longer dry periods and more extreme temperatures are likely to increase the occurrence and intensity of bush fires.

In January 2019, the Huon Valley experienced this firsthand, with large bush fires impacting the region for several weeks. Sensitive vegetation usually too wet to burn (and not adapted to survive fire) became available fuel due to lack of moisture. The 2018–19 summer was Tasmania’s second warmest on record, with the mean temperature 1.6 °C above average. During January 2019, Tasmania only received one fifth of the average rainfall, making it the second driest January on record.

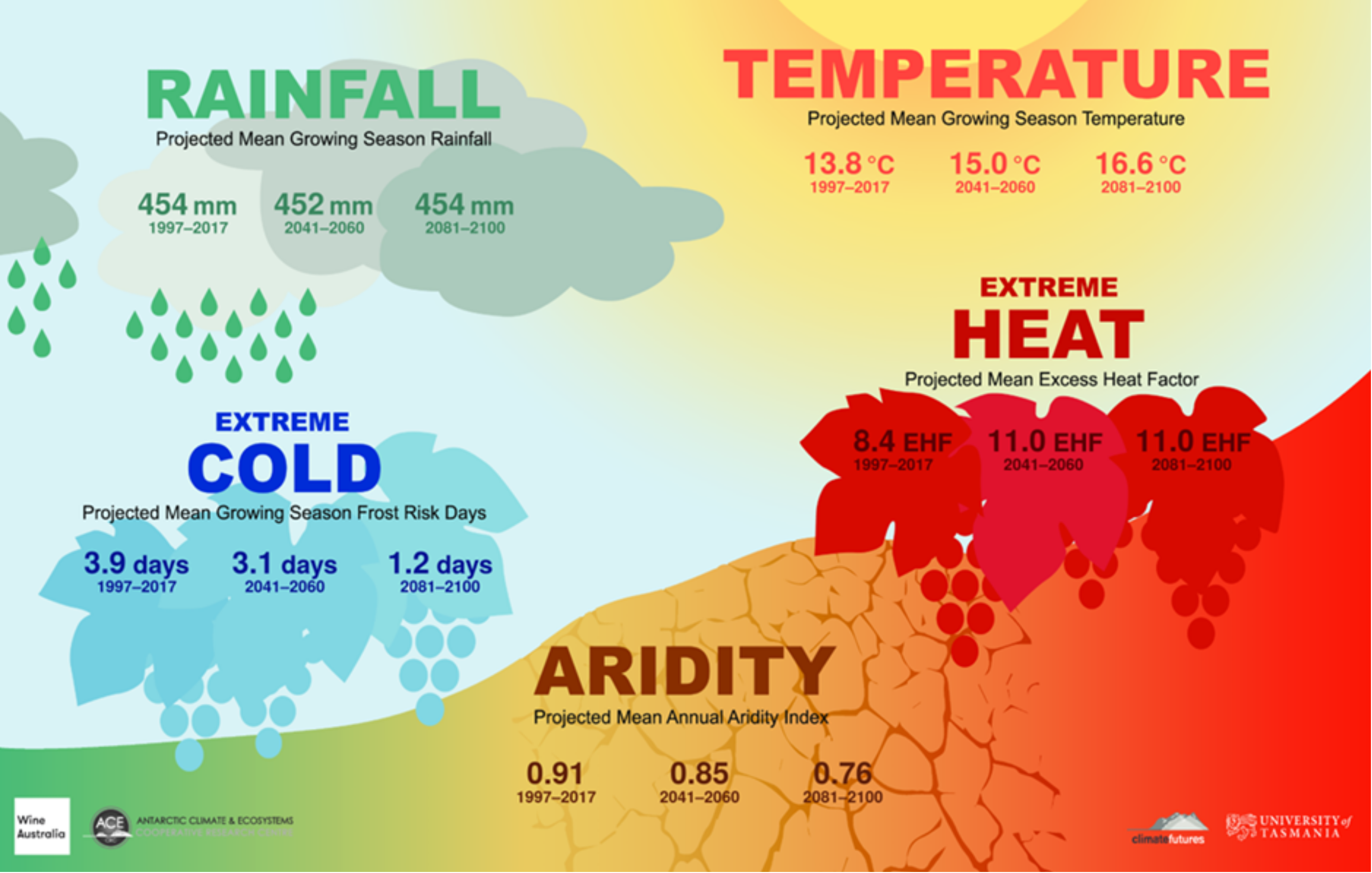

Huon Valley, like the rest of Tasmania, is projected to see:

- A significant change in rainfall patterns from season to season and varying between different regions.

- A rise in annual average temperatures by up to 2.9°C by 2100.

- An increase in storm instances, which is likely to result in increased coastal erosion and inundation.

- Longer fire seasons and more days at the highest range of fire danger.

- More hot summer days and more heatwaves than experienced in the past.

- Substantially reduced incidence of frost.

- An increase in ocean acidification levels and East Coast water temperature by up to 2°C to 3°C by 2070, relative to 1990 levels

- Sea level rise of between 0.39 and 0.89 metres by 2090, although under certain circumstances sea level rises higher than these may occur.

The Regional Climate Change Initiative (RCCI) has prepared regional and municipal climate profiles informed by the Antarctic Climate and Ecosystem CRC and based on the University of Tasmania (UTAS) Climate Futures program outputs. You can watch a presentation on the Southern Tasmanian Councils Future Climate Profile on the Southern Tasmanian Councils Authority website.

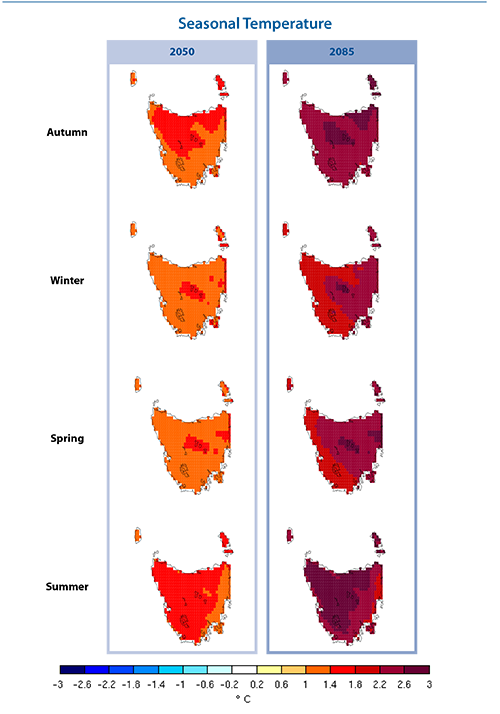

Trends in Tasmania

Under the IPCC’s high emissions scenario (A2), the central estimate of the simulations suggests Tasmania will experience a change in mean temperature of 2.9 °C over the 21st century. The temperature increase for Tasmania under this emissions scenario is less than the projected global warming of 3.4 °C. The projections suggest temperature increases are smaller in the early part of the century, but the rate of change increases towards the end of the century. Under the lower emissions scenario (B1), the central estimate of the simulations shows a rise in mean temperature of 1.6 °C over the 21st century.

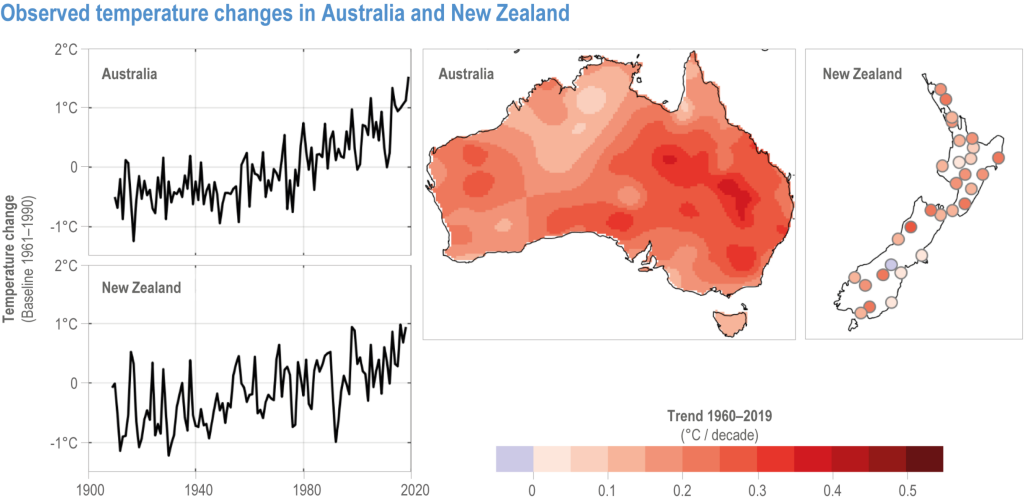

Trends in Australia

Australia has experienced significant climate changes over the past century. Since national records began in 1910, the country’s climate has warmed by an average of 1.47 ± 0.24 °C, with sea surface temperatures rising by 1.05 °C since 1900. This warming has led to more frequent extreme heat events over both land and sea. Additionally, rainfall patterns have shifted, with a 15% decline in April to October rainfall in southwest Australia since 1970 and a 19% decrease in May to July rainfall in the same region. Southeast Australia has also seen a 10% reduction in April to October rainfall since the late 1990s, while northern Australia has experienced increased rainfall and streamflow since the 1970s.

These climatic shifts have had widespread impacts on the environment. Streamflow has decreased at most gauges across Australia since 1975, and snow depth, cover, and the number of snow days in alpine regions have declined since the late 1950s. There has been an increase in extreme fire weather and longer fire seasons across large parts of the country since the 1950s, alongside a decrease in the number of tropical cyclones. The oceans around Australia have acidified and warmed by more than 1 °C since 1900, leading to longer and more frequent marine heatwaves. Sea levels are rising, contributing to more frequent extreme events that pose risks to coastal infrastructure and communities.

Changes Globally

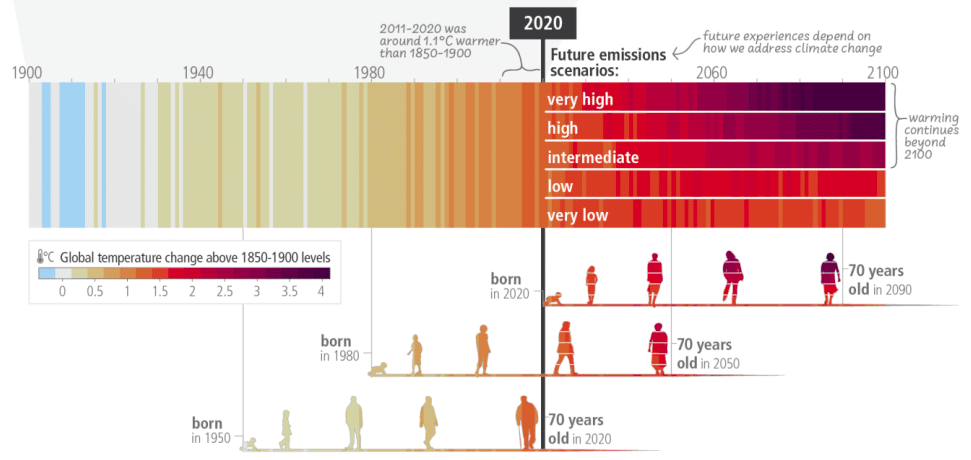

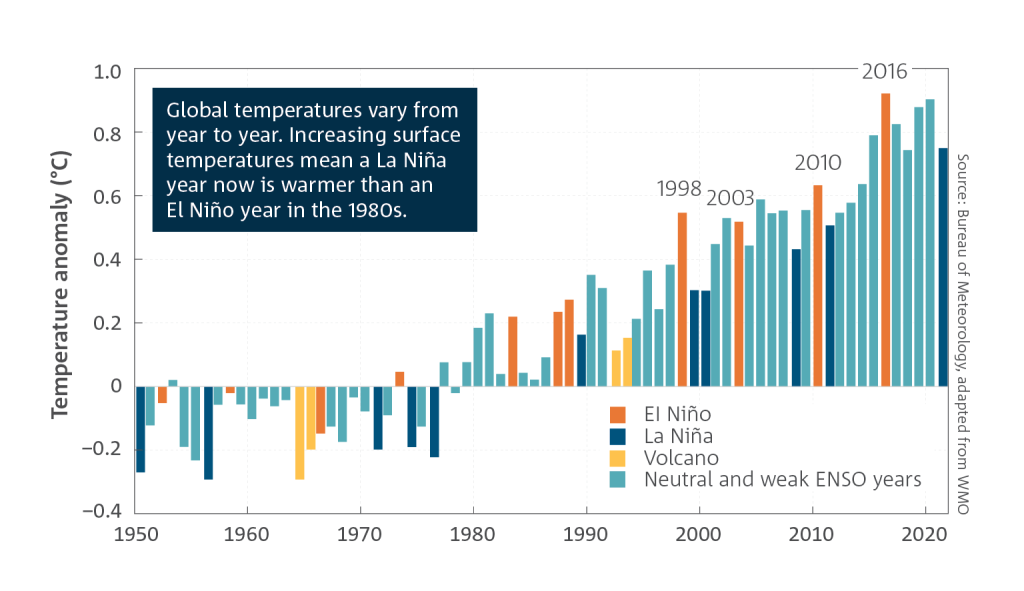

Concentrations of major long-lived greenhouse gases continue to rise, with global annual mean carbon dioxide (CO2) levels reaching 414.4 parts per million (ppm) in 2021 and the CO2 equivalent of all greenhouse gases reaching 516 ppm. These levels are the highest on Earth in at least two million years. The decline in global CO2 emissions due to the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020 had a negligible impact on climate change, as CO2 concentrations continued to rise and fossil fuel emissions nearly returned to pre-pandemic levels by 2021.

The accumulation rates of methane (CH4) and nitrous oxide (N2O) in the atmosphere increased significantly during 2020 and 2021. The global average surface temperature has warmed by over 1 °C since reliable records began in 1850, with each decade since 1980 being warmer than the previous one. The world’s oceans, particularly in the Southern Hemisphere, have absorbed 91% of the extra energy stored by the planet due to increased greenhouse gas concentrations. More than half of all CO2 emissions from human activities are absorbed by land and ocean sinks, which help slow the rate of atmospheric CO2 increase. Global mean sea levels have risen by around 25 cm since 1880 and continue to rise at an accelerating rate.

Future Impact Scenarios

Adverse impacts from human-caused climate change will continue to intensify, affecting both current and future generations. Despite efforts to mitigate climate change, the world is likely to experience significant warming effects for decades. The choices made now and in the near term will determine the extent of these impacts, but even with the lowest emissions scenarios, the effects of climate change will persist and shape the environment for generations. The urgency of addressing climate change is clear, as it influences the future experiences and well-being of people born today and in the coming decades.